Quick Takeaways

- Inaccurate details and anachronisms can pull readers out of the story.

- Overused tropes make the genre feel stale.

- Cultural appropriation and misrepresentation harm authenticity.

- Balancing authorial license with factual truth is tricky.

- Solid research habits and sensitivity readers improve credibility.

When you pick up a novel set in the past, you expect a blend of storytelling and a window into that era. But many historical fiction problems slip through the cracks, leaving readers confused or even offended. Below we break down the most common pitfalls, why they matter, and what writers can do to avoid them.

Historical Fiction is a genre that blends fictional narratives with real‑world past settings, aiming to transport readers while filling gaps with imagination.

The allure is obvious: you get the drama of a novel with the richness of history. Yet that blend creates a minefield of potential issues. Below each problem is linked to a specific entity-an element of the craft that often goes wrong.

1. Inaccurate Details & Anachronisms

Anachronism refers to anything placed outside its proper historical time, such as modern slang in a Victorian setting. Readers with a basic knowledge of the period instantly spot the slip, and that jolt can break immersion. Examples include smartphones mentioned in a WWI story or food items that weren’t introduced until decades later.

Why it matters: Accuracy builds trust. When that trust erodes, the whole narrative credibility suffers, even if the plot is compelling.

2. Overused Tropes & Narrative Clichés

Narrative Tropes are recurring plot devices or character types that become predictable when overused. Think of the “damsel in distress” rescued by a charismatic soldier in every Napoleonic war novel, or the “reluctant historian” who discovers a secret love affair.

Impact: Tropes can make the story feel like a history textbook with a thin veneer of drama, reducing emotional engagement.

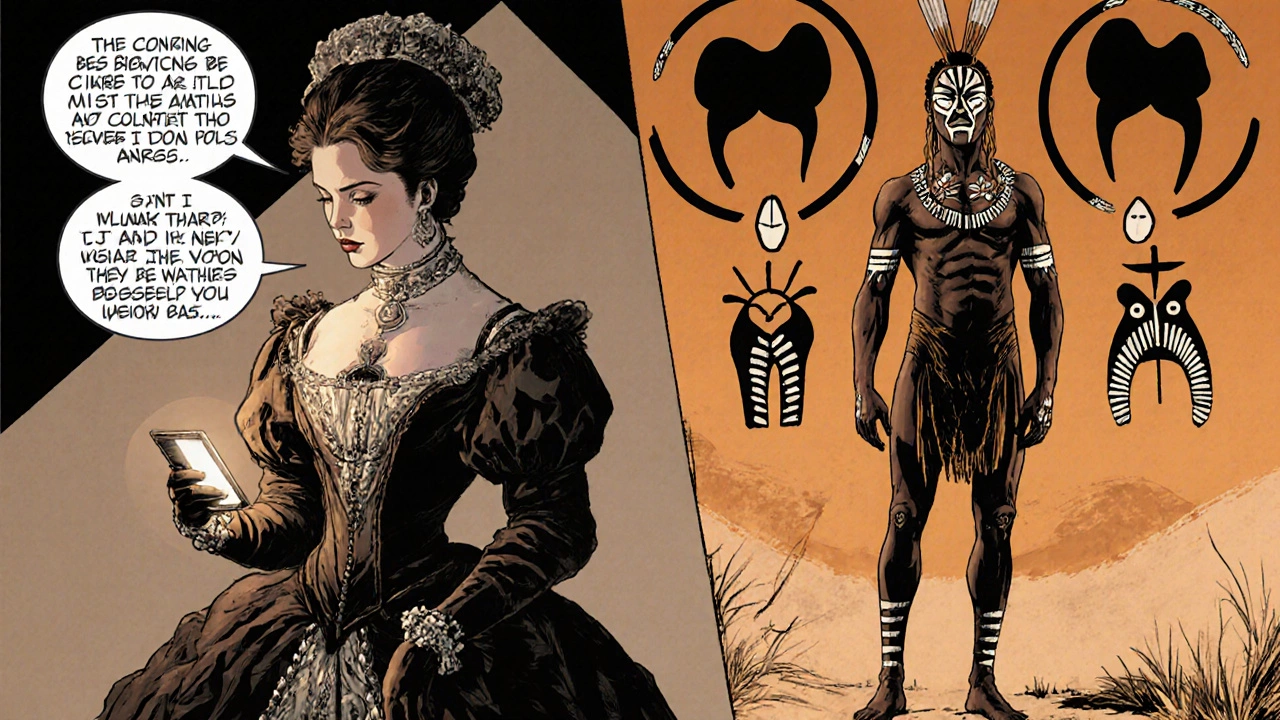

3. Cultural Misrepresentation & Appropriation

Cultural Appropriation occurs when an author from outside a culture writes about it without proper understanding or respect. This often leads to stereotypes, flattened characters, or the erasure of marginalized voices.

Case in point: A Western author portraying Indigenous Australian societies using colonial-era myths instead of contemporary scholarship. Such missteps alienate readers from those cultures and attract criticism.

4. Authorial License vs. Historical Truth

Authorial License is the freedom writers take to alter facts for narrative flow. While some leeway is acceptable, crossing the line into falsehood-like inventing a major battle that never happened-can misinform readers.

Balancing act: Provide a disclaimer or author's note explaining where creative liberties were taken, allowing readers to separate fact from fiction.

5. Inadequate Historical Research

Historical Research involves gathering primary sources, academic texts, and expert interviews to ground the story. Skipping this step often results in cheap errors, like wrong dates, titles, or social customs.

Tip: Keep a research log and cross‑check every detail that influences plot or character decisions.

6. Reader Expectations & Suspension of Disbelief

Reader Expectation is the mental model a reader brings to a book based on genre conventions. When a historical novel fails to meet those expectations-say, by ignoring known gender roles of the era-readers feel cheated.

Solution: Clearly signal the novel’s approach early (e.g., “a historically inspired romance with modern sensibilities”).

7. Pseudohistory & Misinformation

Pseudohistory is the presentation of fringe or debunked theories as factual history. Including conspiracy‑like elements (e.g., “the Queen was a time traveler”) without framing can spread falsehoods.

Readers often take fiction at face value, especially if the book doesn’t label these parts as speculative.

8. Representation & Inclusivity Gaps

Representation refers to the diversity of characters, cultures, and viewpoints within a story. Many historical novels default to white, male protagonists, erasing the presence of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ individuals who lived in those times.

Result: The narrative feels incomplete and perpetuates a narrow view of the past.

How to Mitigate These Issues - Best Practices for Writers

- Start with a research plan: list primary sources, scholarly articles, and experts to consult.

- Create a timeline worksheet to flag potential anachronisms before drafting.

- Use sensitivity readers from the cultures you portray to catch misrepresentation early.

- Maintain a “fiction vs. fact” appendix that cites deviations.

- Rotate character archetypes to avoid trope fatigue-mix seasoned veterans with reluctant heroes, for example.

- Consider a multi‑disciplinary beta‑read group: a historian, a literary critic, and a lay reader.

| Problem | Impact on Reader | Quick Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Anachronism | Breaks immersion | Cross‑check dates, language, technology |

| Overused Tropes | Feels predictable | Subvert expectations, blend genres |

| Cultural Appropriation | Alienates communities | Hire cultural consultants, read native authors |

| Excessive Authorial License | Misinforms readers | Include author's note, label speculative parts |

| Poor Research | Erodes credibility | Maintain a research log, verify with experts |

Mini‑FAQ

Why do some historical novels feel like they’re set in the wrong era?

Often it’s an anachronism. The author may use modern slang, technology, or social attitudes that didn’t exist, which jolts the reader out of the story.

Can I change major historical events for the sake of drama?

Changing key events turns the work into pseudohistory, which can mislead readers. If you must, clearly label those sections as speculative or alternate‑history.

How can I avoid cultural stereotypes?

Hire sensitivity readers from the culture you’re depicting, and study primary sources written by members of that community. Avoid relying on second‑hand tropes.

Is extensive research a waste of time for fiction?

Research grounds your story, prevents glaring errors, and can spark plot ideas you wouldn’t have thought of otherwise. Even a light research habit beats guesswork.

What’s the best way to signal where I took creative liberties?

Include an author’s note or a brief appendix that lists major deviations from the historical record. Readers appreciate transparency.

By keeping these problems in mind and applying the suggested practices, writers can craft historical fiction that thrills readers while respecting the past. The result? Stories that feel authentic, fresh, and responsibly told.